Edited on 5 November 2021.

Other essays about residential lodging in Victorian Houston:

Houston Lodging Project: Abstract

The Language of Housing in Houston

Boarding Houses, Households, Homes, and Families

Residential Hotels and Boarding Houses

I posted a few brief essays about Victorian residential hotel and boarding houses. Hospitality proprietors in Victorian Houston operated restaurants, too. Yet this was an emergent institution. According to Rebecca Spang, restaurants started in France in the late-1700s. In some sense, hotels and restaurants were reactions to old public house traditions. These reactions unfolded differently in the US, England, France, and Germany. Of course, Houston was founded when Texas was an independent nation. At the same time, though, most the culture of the Texas Republic was for most intents and purposes Anglo-American. In addition, Texas was culturally southern. Therefore I will sometimes slip into characteristics of Republican Houston as being American. Legally, it was not. Culturally, many times it was.

The term “restaurant” derives not from a kind of hospitality venue, but from a kind of food. Small shops emerged in Paris in response to a French health fad: thin consummés that were kinder to those with weak stomachs and weak hearts. These weak soups, called restorants, later gave the name to the places where they were served, restaurants. These cookshops were frequented by people of weak constitutions, where they could slowly sip restorants in a semi-public place. Spang quips that the first restaurants were places where people went to barely eat. Restaurants in Paris attracted a broader following, many of whom sought reprieve from the public house, where boarders dined at appointed times at a common table and their choices were restricted to table fare. A restaurant was liberating. These restaurants served a variety of entrees during a large window of service hours. Patrons ordered items from a menu and were billed only for what they ordered. Furthermore, people in public houses boarded at la table d’hôte, French for “table of the host.” This custom had two principle consequences. First, this was in some sense family-style service. Instead of blood relations living in the same house and eating together, the public house “family” ate together. Sometimes this familiarity bred contempt. Where could someone eat to get away from their public house mates? Second, there was the opposite problem: day boarders. Some public houses earned more revenue by serving strangers for a fee, where they boarded at la table d’hôte. These day boarders were vetted by the public house owner, but a public house resident had no control over who might show up at the table that day.

Restaurants evolved into a hospitality type more closely associated with a style of service and less associated with a kind of food. Instead of table d’hôte, where a boarder could be seated with both a familiar source of irritation or a strange new one, restaurants provided small tables, and some even partitioned diners with screens or separate rooms. So a restaurant is where people dined in semi-public places in order to eat in privacy, or rather, where the diner controlled with whom they dined. Restaurants also provided diners more control over what they ate. A boarder at a public house could either accept or decline the food offered at the table. At a restaurant, a diner chose entrees from a printed menu and the food ordered was billed a la carte.

After the restaurant evolved from a type of Parisian cookshop serving soups to a stylish venue with a new mode of service, the concept traveled over the Atlantic. Naturally, New York was the first adopter of the restaurant in the United States. The restaurant was a practical solution for many New Yorkers. Many workers in the early 1800s chose to reside in public houses, boarding houses, and even some hotels based on location. They demanded proximity between work and home. As the developed area of Manhattan grew well beyond Wall Street and an increasing number of people moved uptown, there was also a growing attenuation between work and home. This was also facilitated by the first horse railcar service in the 1830s. With fewer people living in proximity to work, there were fewer opportunities to return home for daytime meals. Restaurants served these downtown workers.

The old tradition of the public house combined lodging, drinking, and meals. According to Sandoval-Strausz, the English public house was mainly in the business of “renting seats” at the bar than it was in the business of selling lodging. England licensed public houses as venues for the legal sale of alcoholic drinks. In exchange for this privilege, public houses were also required to provide lodging to travelers.*

Public house service was characterized by bundling lodging and meals as a single fee; and by serving the same entrees to all guests, at appointed times, and at a common table. In these senses, public houses and boarding houses were similar. But boarding houses required no license because they did not sell alcohol.* Restaurants and hotels were two novel and bifurcating responses to this old type of hospitality. Little is known about the few restaurants that opened in Houston during the Republic. Yet more information about local restaurants emerges during Reconstruction. Houston restaurants after the Civil War, however, did not yet adopt all of the novel service features associated with the restaurants of Paris. Some Houston restaurants offered service at all hours. Although one 1870 restaurant lodged some Houston workers, it was mainly in the business of serving food. Some restaurants sold board per meal, per day, per week, or per month. There is no evidence that these restaurants published menus or charged by the entre, two features of Parisian service.

Restaurants served diners during antebellum and Reconstruction Houston. Restaurants were still a novel type of hospitality, with origins in eighteenth-century France, with the earliest examples in the US located in early nineteenth-century New York. Houston, both a small city and one lying far from the population centers of the northeastern US, trailed in many social trends. Even though restaurants did emerge in Houston, modes of service in Houston kept one foot in the old public house tradition and one foot in the novel restaurant mode.

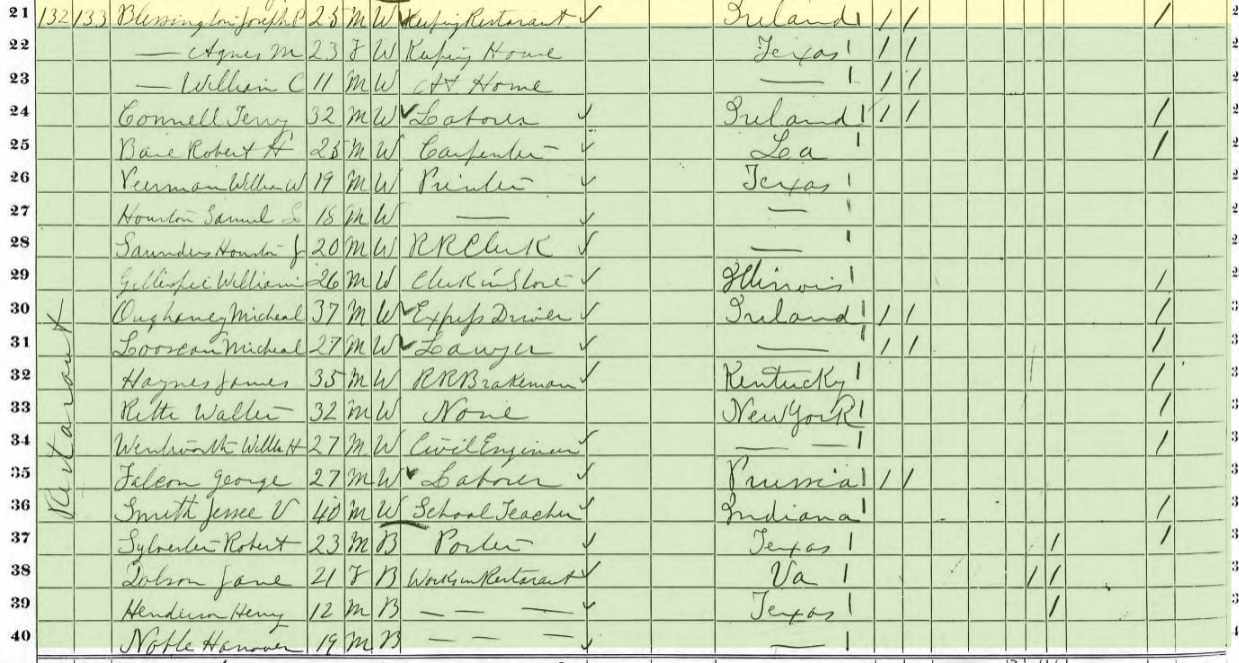

1870 US Census Manuscript Returns, Harris County, Houston, First Ward: this record indicates that the restauranteur, Joseph P Blessington, resided on site. “Our House” restaurant was located on the north side of Congress Avenue between Travis and Main streets, where the Icon Hotel is presently located.

Some restaurants in Reconstruction Houston offered lodging, so in this sense, they were not sharply distinguished from hotels and boarding houses. All three hospitality types offered lodging and prepared meals. However, hotels were often larger facilities than restaurants, featured various common areas, and offered more guest rooms to let. Restaurants featured prepared meals and the few examples in 1870 Houston suggests that their sometimes their lodging facilities were limited, and mainly housed employees. However in 1870, “Our House” restaurant in Houston housed the owner, his wife, a teenaged son, three restaurant workers, and fourteen boarders, with their occupations ranging from common laborer to lawyer. With twenty persons residing in the restaurant, it housed more people than some local hotels, but far fewer people than a hotel which was a little more than a block away. Hutchins House, which was the largest and finest hotel in town for many years, housed eighty persons in 1870. While the distinction between hotels and restaurants was real, the differences between a hotel and a restaurant were very subtle during Reconstruction Houston. If a present-day Houstonian had seen one of these restaurants of Reconstruction Houston, they might remark, “This is not a restaurant, it’s a hotel.”

* Thanks to @82_Streetcar for questions and comments.

References

Andrew P. Haley. Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920 (Chappell Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Mark Kurlansky. The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell (New York: Random House, 2007). Reprint.

Doris Elizabeth King. “The First-Class Hotel and the Age of the Common Man,” The Journal of Southern History 23:2 (1957), 173-188.

Cindy R. Lobel. Urban Appetites: Food & Culture in Nineteenth-Century New York (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Katie Rawson and Elliot Shore, Dining Out: A Global History of Restaurants (London: Reaktion Books, 2019).

A. K. Sandoval-Strausz. Hotel: An American Story (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

Rebecca L. Spang. The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000).