This is an edit of an excerpt from a previously unpublished essay from 2017, “A Brief Roman Social History of Streets and Sidewalks.”

See also:

History of Sidewalks: An Introduction

Abutters’ Responsibilities for Streets and Sidewalks in Ancient Rome

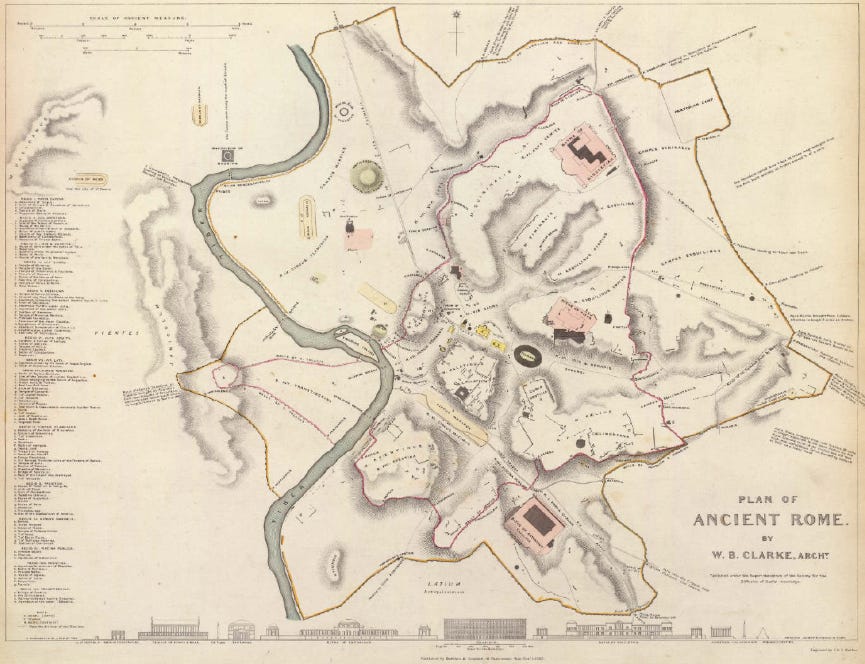

Image 1. W. B. Clarke, “Plan of Ancient Rome,” 1830.

Charles Marohn, founder of Strong Towns, promotes an intuitive notion in American English distinguishing streets from roads. For Marohn, streets are local rights-of-way with high levels of access and economic value; roads are rights-of-way optimized for speed, with low levels of access and low economic value. The strong intuitive pull is palpable through the sensible expressions city streets and country roads, while recombining them as city roads and country streets offends the ear. In ancient Rome, however, there are functional distinctions of streets and roads, but no such distinction is obvious in Classical Latin.1

Several Latin terms described different kinds of easements. Via, platea, angiportum, semita, and vicus cover a great range of urban easements, even if this does not form an exhaustive list.2 We might count all of these as urban easements “streets,” or “urban streets”; that is, any public easement that permits a conveyance of traffic, usually running along a corridor flanked by buildings. Implicit in this definition is the idea that an urban street is framed by development.3 Perhaps Varro anticipated this idea with his analysis of vico:4

In oppido vici a via, quod ex <u>traque parte sunt aedicicia. Fundalae a fundo, quod exitum non habe<n>t ac pervium non est. Angiportum si <ve quod> id angustum, <sive> ab agendo et portu. Quo conferrent suas controversias et quae venderentur vellent quo ferrent, forum appellarunt.

In town there are vici ‘rows,’ from via ‘street,’ because there are buildings on each side of the via. Fundulae ‘blind streets,’ from fundus ‘bottom,’ because they have no way out and there is no passage through. Angiportum ‘alley,’ either because it is angustum ‘narrow,’ or from agere ‘to drive’ and portus ‘entrance.’ The place to which they might conferre ‘bring’ their contentions and might ferre ‘carry’ articles which they wished to sell, they called a forum.

Viae (the plural form of via) can be used as a general term for streets, yet viae can also denote wider streets, or perhaps this sense could be considered as an analog for our contemporary term, “major thoroughfares.”5 Another possible definition of via is, “a type of wide street often equipped with colonnades and decorated with statues.”6 The Twelve Tables (c. 450) prescribed at least eight feet in width for a via, and sixteen feet in width for curves, wide enough to allow meeting carts to pass.7 Streets in Rome fitting these dimensions include Via Lata, Nova Via, Sacra Via, and Via Tecta.8 Viae also denoted wide intercity roads running from Rome’s gates to other cities in Italy.9 Romolo Staccioli claims that via was a term assigned only to roads designed for intercity travel. The Nova Via and Sacra Via, he explains, were originally constructed outside the city gates, but occupied areas that were later incorporated by Rome.10 Alan Kaiser concurs that “intercity road” conveys the original meaning of via, but adds that the term was later applied to at least a few city streets. Kaiser also notes that via referred to any street which led to a city gate. Theodor Mommsen, according to Cornelius van Tilburg, also perceives two main senses of the term via: either as a general conveyance, or as a conveyance principally for drivers.11 However, van Tilberg’s own view encompasses seven types of viae, with each use of via accompanied by a qualifier. These qualifiers include consularis, militaris, praetoria, privata, plostralis, publica, and vicinalis. Four of these—consularis, militaris, praetoria, private—he defines in terms of who built them, and thus, who controlled them. Via plostralis and via publica are both defined in terms of who can use them, and via vicinalis is a local road connecting two other roads, which is defined in terms of function.12

Almost all references to streets which led to fora employed the use of via or plateia, with the notable exception being a passage from Cicero. In this case, Cicero disparaged his enemy Verres by associating statues bearing his likeness with the term angiportum.13

Angiportum denoted a social distinction with via. An angiportum (as was a semita) was narrow, and also was associated with less light. So any social or economic transaction in a via connoted legality and transparency, contrasting with the connotation of similar activities in an angiportum as being secretive, corrupt, or a place for criminal activity. Thus Cicero tells his readers that Verres placed his own statues along various angiportae in Syracuse, “where it is hardly safe to go.”14 This leads us to ask how much Cicero was merely acknowledging prevailing attitudes of Romans toward viae and angiportae and how much he was trying to exploit these attitudes. Likewise, Cicero might have been expressing these notions in terms of elite perception. For example, Livy and Apuleius used the terms angiportae and semitae to refer to the locations of shops and ateliers, but epigraphical records provide many examples of commerce taking place on viae.15

In contemporary times, a street type is revealed as a part of its name, i.e.: the East Side Highway and the Long Island Expressway in the New York area, and Boulevard Champs-Élysées and Rue Mouffetard in Paris. Few Roman street names are conveyed through classical literature, and some scholars believe that most streets were either unnamed or unmarked.16 By contrast, what I call “highways,” or roads between cities, did typically bear names.17 This creates inscrutability in reference to the street system of Rome. While some of the ancients invoked a named street, we do not always know how to locate it, and at other times, archaeologists have located a stratum of pavement, but we cannot be certain about the classical name for it. Is the discovery of pavement one of the few urban streets named by the ancients, or should archaeologists assign a modern name to it?18 In the end, how do we identify streets, and how do we write a history for the streets and the street network?

The ancient references to interurban roads are clear. The first of these highways and also the most famous, the Via Appia, was built in 312 BCE and named for one of the censors, Appius Claudius.19 The first segment of the Via Appia runs from Rome in a southeasterly direction to Capua. Livy is not explicit about any pavements, “Appi, quod viam munivit et aquam in urbem duxit,” or “Appius…built a road and conveyed a stream of water into the City,” according to one translation.20 Lorenzo Quilici thinks this stretch of road was paved with gravel, because of the phrase viam munivit, which he translates as “protected the road.”21 Laurence believes the initial road was paved with compacted gravel, and dismisses the possibility that it was paved with stone in 312 BCE.22 Many segments of the Via Appia may have included curbed sidewalks paved with packed gravel with widths varying between three and nine feet, and periodic stone blocks placed between the roadbed and sidewalk to guard against careening carts.23

The Romans, although prolific in laying down good highways, were preceded by the Mesopotamians, Greeks and the Persians. Archaeologists have dated some roads near Nineveh circa 2600 BCE, and have found ancient asphalt pavements in Babylon. The Persians built a long “Royal Highway” stretching from Persepolis to Sardis. Ancient Greek highways are evident in Crete, Mycenae, and Hellena. The Greeks used a general term for roads (ὁδός), and a more specialized term for roads capable of conveying vehicles (ἁμαξιτος).24 Some ancient sources credit Roman road building techniques to the Carthaginians, but contemporary scholarly consensus attributes them to the Greeks and Etruscans of southern Italy.25

The first urban streets of Rome were trenches cut in the earth, with the surface finished by ramming dirt into place.26 Rome prioritized the engineering and paving of highways over urban streets.27 That is not to say that Rome did not maintain easements within its boundaries. The first example of paving in Rome was the ramming of dirt in the forum around 600 BCE, marking the early urbanization of the valley between the Capitoline and the Palatine.28 Livy, referring to 295 BCE, writes, “semitamque saxo quadrato a Capena porta ad Martis straverunt,” or “They also made a paved walk of squared stone from the Porta Capena to the Temple of Mars,”29 perhaps the first Roman street clad in high-quality material. Ray Laurence argues that stone of the region was difficult to split into blocks, so these pavements were noteworthy. It stands to reason that Livy would have specified stone pavements had they been used earlier than 295 BCE.30 As a point of terminology, Eric Poehler claims that Vitruvius innovated the uses of nucleus, pavementum, rudus, and stratum. According to this account, these terms had been used to refer to floor treatments within building interiors, but Vitruvius also used them to refer to street pavements. Some early modern readers of Vitruvius started attributing the usages of these terms to common ancient Latin. Instead, the only common ancient terms are silex (stone pavements) and glarea, for any treated road surface, including silex, gravel, and rammed-dirt. The archaeological record identifies a total of 29 layers of surfaces in the Forum.31

City streets were perhaps paved over a long period of time during the 3rd century BCE.32 As noted above, Livy reports a paving project from Porta Capena to the Temple of Mars in 295 BCE (10.23.12–13). The starting point of Porta Capena implies that this street was contiguous with the Via Appia. Furthermore, it was an urban street which cut through central Rome, and then to the other side of the city, terminating at the southern Campus Martius.33 Livy referred to this street as a semita, probably indicating that this was a narrow easement. Less plausibly, it could also mean that raised sidewalks were paved and the trenched roadbed was not. Livy claims that the clivus publicus, an inclined-street, was paved in 238 BCE. Paving assisted vehicles in climbing the Aventine hill, the location of many industrial and warehouse sites.34 In 189 BC, censors approved a project to pave to same street in silex, and fifteen years later they started a general program to let contracts for paving city streets.35 According to Kaiser, intercity highways were carefully constructed of different layers of stone:36

decreasing in size as they neared the surface and a top layer of dressed stones fitted together in a bed of mortar. Urban streets, on the other hand, usually consist of a shallow bed into which a leveling layer of rammed earth and stone was laid and topped with either stone, gravel or cobbles mixed with clay, silt, or sand.

Recalling that Varro associates vici (plural of vicus) etymologically with via, and associates the structure of vici with “rows” formed by the buildings: “In a town there are vici ‘rows,’ from via ‘street,’ because there are buildings on each side of the via.”37 Earlier in Book Five, Varro makes an association between movement and farming, which might be a clue to interpreting the rows of buildings: “Quare non, cum de locus dicam, si agro ad agrarium hominem, ad agricolam peruenero, aberraro,” or “For this reason, if, I speak of places, I move from field [agro] to an agrarian man [agrarium hominem], and arrive at a farmer, I still won’t have gone astray.”38 Diana Spencer argues for a semiotic relationship between movement, place, farming, and the field:39

The act of speech, in particular for Varro’s rhetorically trained audience, who in effect ‘spoke’ for a living, equals a purposeful movement towards a destination. This passage presents the terminology of linguistics in two ways: as familial analogy (ager and its offspring) and as a rabbit-hole to Rome’s ideal rustic roots, a time when all citizens worked the land and gained definition from its limits—as Cato’s second-century BCE cliché has it, the best compliment for a Roman was to call him a farmer, and Varro himself picked up on this in his earlier survey of what makes Roman agriculture tick. This passage also proposes and intimate connection between place, space (a place which enables or is defined by movement), and human identity. Ager signifies both ‘field’ and ‘territory’.

Having demonstrating his interest in farming as a metaphor (5.13), did Varro imagine the rows of urban buildings along the vici (5.145.1) as a metaphor for crops? Might this be an association with urban places and buildings as their products? Varro considers other urban street forms. According to Spencer, he associates the second part of compound form of angiportum (portum) with portus (a gate), but considers two etymologies for “angi-“, angustum (narrow), and agere (to drive), though it seems that the most natural reading for angiportum would be “a narrow passage.”40

Vico or vicus is more difficult to discern. Varro (De Lingua Latina 5.145.1) classifies a vico as an urban type of via, where it appears that Varro also uses via as a general term for streets and highways. Does Varro employ differing definitions for via based on whether it is used in a rural or urban context? If so, then the urban definition of via might be compatible with a vico as a type of narrow street. We will see other examples of vico used to refer to a narrow street. In addition to “narrow street,” vicus has other meanings. A vicus can refer to a village.41 A very important meaning is for an urban neighborhood,42 as both Caesar and Augustus adapted the term for small administrative units for Rome.43 In addition to these uses of vicus as narrow street, village, and neighborhood, Kaiser alleges that it is used to refer to a wide street. A Vulgate translation of Matthew 6.2–5 used it as a synonym for platea, while Varro, Juvenal, Livy, and Ovid all observed carts traveling on what they called vici. (Check for references on usage.)

J. Bert Lott offers a competing interpretation of vicus. Varro defined it in three ways, but none of these referred to a street or road: they all were references to clusters of dwellings. In addition to Varro De Lingua Latina 5.145 and 5.159, Lott introduces opinions from two later grammarians. In the second century CE, Sextus Pompeius Festus recorded the thoughts of Verrius Flaccus, a writer from the Augustan era. This hybrid of Varro and Flaccus, as expressed by Festus, put forth three definitions of vicus. First, there is a rural vicus, where multiple farms in relative proximity are considered as a group. A modern sense of this idea might be expressed by the English “village.” Two other definitions consider urban vici: buildings aggregated within a town, especially as a block face; and the other is simply as a term for an apartment building. Isidorus of Seville, a seventh-century bishop, conceived of both a rural and urban type of vicus based on his reading of Varro and Flaccus, “Urban dwellings themselves, as I said earlier, make up a vicus. The inhabitants of a vicus are called vicini.44 Streets (viae) are the thin spaces in the middle of vici.45 Lott summarizes these ideas:46

From these comments, we can conclude that the vicus comprised the dwellings on either side of the street, not the street itself. It was closely associated with the inhabitants of the dwellings, called collectively vicini. Since they did align closely with streets, ancient authors often use vici to give directions or describe a route through the city streets, but this is evidently a secondary usage derived for convenience. Vicus was not synonymous with street, as is made by the fact that most vici did not run the entire extent of a city street, but we must be careful not to confuse a purely topographical reference to a vicus with one that means to include the associative social elements of a neighborhood. Nevertheless the basic use explicitly refers to a group of dwellings and their inhabitants; that is to say, it refers to a neighborhood that was both a social and geographical entity.

How does Lott’s interpretation with vicus square with other literary examples? Returning to Martial (7.61) [I cannot see where Lott addresses this passage!], for example, confirms the contrast of via as a wide street and vico as narrow one, when he praises Domitian for issuing an edict which proscribed the encroachment of shops into the street, “You bade the narrow streets expand [crescere vicos] and what had lately been a track [semita] became a road [via].”47 There is no way to read this line in which vicos refers to anything but the space between the buildings. Martial uses vico and semita for a track or narrow street, and he uses via for a wide street.48 Martial may also associate semitae with commercial streets.49 Tacitus may have implied vici were narrow when he claimed these streets allowed the flames to jump from block to block during the Great Fire of 64 CE. Looking at the text of the Annals, “The blaze in its fury ran first through the level portions of the city, then rising to the hills, while it again devastated every place below them, it outstripped all preventive measures; so rapid was the mischief and so completely at its mercy the city, with those narrow winding passages and irregular streets, which characterised old Rome.”50 The Latin text reads: [I]mpetu pervagatum incendium plana primum, deinde in edita adsurgens et rursus inferiora populando, antiit remedia velocitate mali et obnoxia urbe artis itineribus hucque et illuc flexis atque enormibus vicis, qualis vetus Roma fuit.”51 Though not being a Latin reader, a translation for “illuc flexis atque enormibus vicis” as enormibus can mean either large or irregular. However, with flexis, it is plausible that Tacitus intends that the vici were “twisting and irregular.” Here, Lott’s reading of urban vici as the rows of dwellings makes sense because Tacitus is describing the path of the fire. It also calls into question the English translation, which tells how the flames jumped from block to block. Vicus in this context could refer either to the narrow width between the buildings, or refer to the irregular paths of the building rows.

In this example, however, can vici be reasonably interpreted as either the streets over which the flames jumped, or as the flames running along and consuming each row of buildings. Kaiser, on the other hand is perplexed by this narrative of Tacitus, whom he reads as having used vici to point out the narrow streets, but followed up with a usage of vici to bring attention to the straight and wide streets planned by Nero after the fire.52 Kaiser translate the phrase, “enormibus vicis” as “wide streets” (from enorme, “large”). As I have argued above, flexis is a cue to translate enormibus as “irregular” and not as “large” or “wide.” Therefore, his idea that a vicus can sometimes mean a “wide street” is based on the misreading of Tacitus Annals 15.38, therefore we should dismiss this idea.

Kaiser identifies several Roman street types with no straightforward translation to English. For example, gradus and scalae both refer to stairways. A clivus is a street running up and down a slope, which might lead one to consider “ramp” as a translation. This would have been an important concept for a society whose transportation depended on animal power, and would have also been useful term for wayfinding. Another counterintuitive notion to the contemporary anglophone is the inclusion of gradus and scalae as parts of a street system. Likewise, if there is an instance of a clivus functioning like a ramp, it would be counterintuitive for an Anglophone to think of this as a component of a street system. Moreover, English does not have any terms which designate streets on a slope. The Latin fundula refers to a dead-end or a cul-de-sac.53

Trame might be another street-type and appears to refer to footways or paths, though a term I have not seen in my survey of the secondary sources. Martial, giving directions to a bookseller, writes, brevis est labor peractae altum vincere tramitem Suburnae (Martial Epigrams 10.20.4-5). Tramitem is the singular accusative form of trame. Walter C. A. Ker translates the passage, “Once through Subura, the effort of climbing the uphill path [tramitem] doesn’t take long.”54 Though Martial specifies the way up the hill, there were other terms he might have used, such as clivus or scala.55 This is the only Latin word for street for which I have seen no mention in my survey of the secondary literature.

For the Romans, “streets” do not imply vehicular access. Obviously, neither carts nor wagons can travel on stairways (scalae), and only via and plateae are assumed to have enough room for vehicles.

Two ancient terms for streets have a strong association with surveying rural areas and colonies: cardo (plural cardines), or the streets laid out on a north–south axis; and decumanus (plural decumani), or the streets laid out on the east–west axis. However, there is no reason to suppose that these were common terms for streets among the ancients. Instead these were technical terms put into use for those who divided land for new towns and military camps. We should not suppose these were common terms for streets in the Latin vernacular of commoners or elites.56

Most Roman streets were narrow, with only a few measuring more than eight-feet in width. To hang flesh and bones on these street widths in the ancient world’s largest city, denizens of upper floor apartments might have been able to converse across the way, or even have been close enough to reach across and touch hands.57 By contrast, Americans consider eight feet to be an unacceptably narrow width for a single traffic lane, with ten and eleven foot lanes extant on most streets and roads, and twelve feet to be the standard for highways. The AASHTO Green Book, the book of engineering standards published by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Engineers, recommends that all traffic lanes conform to widths of ten to twelve feet, but many engineers and street planners push for twelve foot lanes.58 With multi-lane highways containing wide lane-widths, a whole Roman neighborhood, or even whole towns, could be nested within some American transportation corridors. For example, at least one segment of Interstate-10 running through west Houston is 26 lanes wide.59

Charles Marohn, “Engineers Should Not Design Streets,” 6 May 2021, Strong Towns.

Alan Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks (London: Routledge, 2011), 30. For further discussion of street types, see also Kaiser, “What was a via? An Integrated Archaeological and Textual Approach,” in Pompeii: Art, Industry and Infrastructure, Eric Poehler, Miko Flohr, and Kevin Cole, eds. (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2011), 115–130; Holleran, “Street Life of Ancient Rome,” in Rome, Ostia, Pompeii: Space and Mobility, Ray Laurence and David J. Newsome, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 247; Romolo Augusto Staccioli, The Roads of the Romans (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004) 11–19; Diane Favro, The Urban Image of Augustan Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 288 n.20; Phillip W. Harsh, “’Angiportum,’ ‘Platea,’ and ‘Vicus,’” Classical Philology 32 (1937): 44–58; Cornelius van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion in the Roman Empire (London: Routledge, 2007), 7–9.

Marohn, “Engineers Should Not Design Streets.”

Varro De Lingua Latina 145, Roland G. Kent, trans. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938).

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 30; “What is a via,” 117.

Kaiser, “What is a via,” 116.

Joseph E. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 188, citing Varro, De Lingua Latina 7.15. See also Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 56, 71; Alan Kaiser, “Cart Traffic Flow, in Pompeii and Rome,” in Laurence and Newsome, 184; Claire Holleran, “The Street Life of Ancient Rome,” in Laurence and Newsome, 247; Diana Spencer, “Movement and the Linguisitic Turn: Reading Varro’s De Lingua Latina,” in Laurence and Newsome, 65; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 7, 27; Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Change (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 1999) 15, 58.

Holleran, “The Street Life of Ancient Rome,” 247. Cf. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City, 188, counts only the Sacra Via and Nova Via as viae. See also Staccioli, Roads of the Romans, 15; van Tilberg, Streets and Congestion, 31.

Stambaugh, Ancient Roman City, 188. For more about the Via Appia, see Lorenzo Quilici, “Land Transport, Part 1: Roads and Bridges,” in The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, John Peter Oleson, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 553–6; Staccioli, Roads of the Romans, 60-63; Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 13–20; Elizabeth Macauley-Lewis, “City in Motion: Walking for Transport and Leisure in the City of Rome,” in Laurence and Newsome, 267.

Staccioli, Roads of the Romans, 17.

van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 7.

van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 7–8.

Kaiser, “What was a via,” 117.

Loc. cit. Find citation to Cicero.

Kaiser, “What was a via,” 118.

Mary Beard, Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008), 110; Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 34; Favro, Urban Image of Augustan Rome, 5, fn. 10 at 282; Harsh, “Angiportum, Platea, and Vicus”; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 50–1; Roger Ling, “Stranger in Town: Finding the Way in an Ancient City,” Greece & Rome 37, no. 2 (1990): 204.

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 34.

For an example of inscrutability regarding both a named street (Nova Via) and unnamed (later named, “Graecae Scalae”) street, see Henry Hurst and Dora Cirone, “Excavation of the Pre-Neronian Nova Via, Rome.” Papers of the British School at Rome 71 (2003): 17–84; T. P. Wiseman, “Where Was the Nova Via?” Papers of the British School at Rome 72 (2004): 167–183; Henry Hurst, “The Scalae (Ex-Graecae) above the Nova Via.” Papers of the British School at Rome 74 (2006), 237–291.

Quilici, “Land Transport, Part 1,” 553–4, citing Livy 9.29; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 5.

Livy 9.29.6; B.O. Foster, trans. Livy, Volume IV, Books VIII–X. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.) Citation taken from Holleran, “Street Life of Ancient Rome,” 248; Quilici, “Land Transport, Part 1,” 553–4; Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 65; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 5.

Quilici, “Land Transport, Part 1,” 555.

Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 15, 65, citing Livy 10.23; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 176.

Quilici, “Land Transport, Part 1,” 553–4, citing Livy 9.29.6; cf. van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 176.

van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 2. Refer to n.13 at 175 for more on Greek terms, where he cites V. Chapot, Dictionaire des antiquités grecques et romaines d’après les textes et les monuments, Volume V. (Paris: 1877), 778. Though Aristophanes complained about mud in Athenian streets, van Tilberg also writes, “Main streets in the Hellenistic cities were wide and well-paved,” compare van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 3 and 4.

van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 4.

Staccioli, Roads of the Romans, 17.

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 48.

Filippo Coarelli, Rome and Environs, James J. Clauss and Daniel P. Harmon, trans. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014), 44.

Foster, trans., Livy 10.23.12–13, cited by Quilici, “Land Transport, Part 1,” 555; Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 64.

Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 65.

Eric E. Poehler, Traffic Systems of Pompeii (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 12–3; Albert J. Ammerman, “Origins of the Forum Romanum,” American Journal of Archaeology 94, no. 4 (1990): 627-45.

Ray Laurence, “Towards a History of Mobility in Ancient Rome (300 BCE to 100 CE),” in The Moving City Processions, Passages and Promenades in Ancient Rome, Ida Östenberg, Simon Malmberg, and Jonas Bjørnebye, eds. (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 183.

Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 19. For more on the significance of the Porta Capena, see David J. Newsome, “Introduction: Making Movement Meaningful,” in Laurence and Newsome, 26–30.

Laurence, “Towards a History of Mobility,” 183.

Laurence, Roads of Roman Italy, 64. Poehler, Traffic Systems of Pompeii, 12 claims that silex is a general term for stone pavements.

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 48. See also van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 15–6.

Varro De Lingua Latina 5.145.1 cited in Spencer, “Movement and the Linguistic Turn,” 70, 72, 77; “Urban Flux,” 103–4. This line from Varro is also cited by Hartnett, “Si quis hic sederit: Streetside Benches and Urban Society in Pompeii,” American Journal of Archaeology 112, no. 1 (2008): 110 n66; Lott, “Regions and neighborhoods,” 179. While Varro uses “rows of houses” as the etymology, no other ancient source uses the term this way, according to Harsh, “Angiportum, Platea, and Vicus,” 52.

Varro De Lingua Latina 5.13, citation and translation from Spencer, “Movement and the Linguistic Turn,” 58 with fn. 6.

Spencer, “Movement and the Linguistic Turn,” 58 with fn. 7.

Varro De Lingua Latina 5.145.2–5, citation and argument from Spencer, “Urban Flux,” 105.

J. Bert Lott. The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 13.

For example, Lott, The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome; Holleran, “Street Life of Ancient Rome,” 247; Diana Spencer, “Urban Flux: Varro’s Rome-in-progress,” in Östenberg, Malmberg, and Bjørnebye, 103; Laurence, “Towards a History of Mobility,” 176.

Lott, The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome, 62–5, 81–97.

Cognate with vecinos (Spanish), vicinato (Italian), voisins (French), and vecini (Romanian).

Lott, The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome, 13–14, ns. 4–9 at 221–222, citing Varro De Lingua Latina 5.145, 5.159; Festus 502, 508L. Quote of Isidorus Etymologiae 15.2.22 provided by Lott, 14.

Lott, Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome, 14.

Martial Epigrams 7.61.

For comments on Martial Epigrams 7.61, see Ray Laurence, “Towards a History of Mobility,” 181; Holleran, “Street Life of Ancient Rome,” 248; Hartnett, “Power of Nuisances,” 138; Newsome, “Making Movement Meaningful,” 45; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 133; Victoria Rimmel, Martial’s Rome: Empire and the Ideology of Epigram (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 24–5; Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 20; J. P. Sullivan, Martial: The Unexpected Classic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1991), 39, 145.

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Systems, 40.

Tacitus Annals 15.38.

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Systems, 33, 212–3, n.180–188, citing Varro De Lingua Latina 5.159; Livy 1.48.5–7; Ovid Fasti 6.601–610; Juvenal Satires 3.232–248. For vici as neighborhoods and Augustan administrative units, see Lott, “Regions and Neighborhoods,” in Erdkamp, 169-89.

Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Systems, 26–8, 211 n. 97–100. Cf. Harsh, “’Angiportum, Platea, and Vicus,” 51, fn. 16; For Varro on the fundula, see Spencer, “Urban Flux,” 104–5; van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 8.

Walter C.A. Ker, ed. and transl., Martial Epigrams, Volume II (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), Martial Epigrams 10.20.4–5. Cf. Luke Roman, “Martial and the City of Rome,” The Journal of Roman Studies 100 (2010), 105. Roman renders the same text as, “It is quick work, once you have crossed the Subura, to overcome the steep path [tramitem].” See also Sullivan, Martial: The Unexpected Classic, 54, 61, 219, 263.

Holleran, “Street Life of Ancient Rome,” 247; Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Systems, 26–8. For several examples of the use of “clivus,” see Staccioli, Roads of the Romans, 12–5; Newsome, “Movement and Fora in Rome (the Late Republic to the First Century CE),” in Laurence and Newsome, 295.

van Tilberg, Traffic and Congestion, 15; Kaiser, Roman Urban Street Networks, 2–3, 24–5.

Stambaugh, Ancient Roman City, 184; Newsome, “Making Movement Meaningful,” 38 with fn. 119, citing Martial Epigrams 1.86.

AASHTO standards are cited in Jeff Speck, “Why 12-Foot Traffic Lanes Are Disastrous for Safety and Must Be Replaced Now,” City Lab, 6 October 2014.

Carol Christian, “Bragging rights or embarrassment? Katy Freeway at Beltway 8 is world's widest,” Houston Chronicle, 13 May 2015.

Thanks for commenting and cross-posting! I am completely self-taught on this, so I am imagining that I could be wrong about some details and that I might be missing some big-picture stuff. Thanks for sharing these etymologies. I am probably missing some important syncretic aspects of Roman culture given my focus on Roman Italy.

I found that very interesting, thank you. I learned a lot of valuable information, which I shall appropriate (with due reference, naturally) for further use!

One of the things that first piqued my interest in Roman history, growing up in the most rural of rural Wales, was that the Welsh language has appropriated words for things like 'street' (Welsh - 'ystrad' from 'strata') that are obviously Romanized urban concepts. The Welsh word for 'road' (heol) is not Latin, and this suggests that the pre-Roman Britons had no concept of urban layout until the Romans came along. Roads might lead from one settlement to another, but once you got there, there were no terms for the lanes and byways in a settlement. The Welsh for 'lane' is 'lon', another non-Latin word that describes something outside of an urban context.

It goes to demonstrate how things as subtle as the concept of a street, and hence urban planning, were part of the Romanization process.

Great article!