A Brief History of the Technological Development of the Bicycle

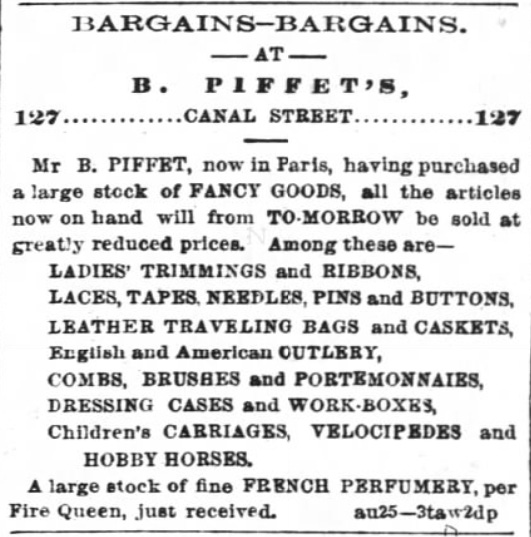

Image 1. 1867 New Orleans advertisement for a large stock of fancy goods, including hobby horses and velocipedes (boneshakers). Image source: Newspapers.com.

Boneshakers in New Orleans

Interest in bicycles in New Orleans was evident as early as September 1867, during the emergence of the boneshaker. B. Piffet on Canal Street advertised both hobby horses and velocipedes for sale that year. Piffet placed a new advertisement for his store in December, including the velocipedes, a second time. One editor reported seeing, “One very determined young gentleman capsized about fifteen times,” but predicted, “we expect to see these toy like wagons supersede the buggies and carriages now in use.” Even a trendsetter such as New York City anticipated New Orleans with its adoption of the velocipede only by some months.1

The boneshaker was a fad, as it was a difficult machine to operate. Since the cranks were attached directly to the front wheel, cranking and steering at the same time required a management of conflicting forces. Interest in boneshakers in the Northeast and in New Orleans petered out within a year or two. Interest in the boneshaker in Houston was almost all talk. There is little evidence that any boneshaker was ever present in Houston, much less mounted. There is only one incident that ties the existence of any boneshaker to Houston, and even that is doubtful. Promoters of the second Texas state fair announced a velocipede race as one of the events. The Second Grand State Fair of the Agricultural, Mechanical and Blood Stock Association of Texas was located on property on Main Street in Houston near McGowen Street, many blocks south of the developed area of town. The race was scheduled for Wednesday, 24 May 1871. While announced, there is no extant report of such a race after the fact. The best interpretation of the available facts is that the race was cancelled due to torrential rains, which turned any possible race course into an unsalvageable quagmire for the remainder of the fair. According to the published itinerary, the fair was to sponsor a velocipede race on its third day. The organizers invited Horace Greeley to speak on opening day, Monday, May 22. A visitor from Dallas complained that the fair opened two days behind schedule, and the fairgrounds were poorly drained and mired in mud. Greeley’s speech was postponed until May 24. Numerous reports of Greeley’s speech appear in various newspapers, but there is no known account of the velocipede race. Therefore, there was no shortage of reporting on the fair which might explain the omission of a report of the velocipede race.2

In its report for May 24, 1871, the day the bicycle race was scheduled, a Galveston newspaper reported, “Nothing of special interest on the grounds to-day. They were, however, crowded all day, and it was difficult to make your way into the halls.” The fair was well-attended that day, and there is no mention of rain. No extant newspaper reports of the State Fair mentioned a race, or even its cancellation.3

There is a surviving report from Houston in 1875 referring to a sighting of what might have been a bicycle. “A silver-haired gentleman having the occasion to enter a store in the Second Ward, left his horse and carriage unhitched in the street in front. While the old gentleman was inside, a gamin came dashing past on a velocipede. This frightened the horse, and a general smash-up and overturning of the vehicle resulted.” Yet, velocipede could have a double meaning. Some people used it to refer to hobby horses in addition to boneshakers. Therefore, this report of a child on a “velocipede” could refer to a hobby horse or a boneshaker, making this report indeterminant regarding the use of a boneshaker in Houston. It should also be noted that this report in 1875 was about four or five years after the boneshaker fad in other parts of the US. At best, this story, even if it were determined that this waif were riding a boneshaker, it was not regarded to be more than a children’s toy.4

New Orleans Slowly Adopts the High-Wheeler

The next evolution of the bicycle was the ordinary. Albert Pope was the first to successfully market high-wheelers in the US, which he first tested at the Philadelphia Exposition of 1876. Pope started importing these machines from England and selling them in the US in January 1878. Later in the year, he contracted with Weed Manufacturing to produce fifty high-wheelers at its factory in Hartford. Pope sold these bicycles under the Columbia brand. By the end of the year, he sold over ninety bicycles in the US and about a thousand in 1879. The penny farthing increased in popularity in the Northeastern US through the 1880s.5

The boneshaker fad, which peaked between 1869 and 1871, reached New Orleans quickly, but these machines were not in use at this time in Houston or Galveston, though it is possible that they were marketed as recreation for children. The high-wheeler had a modest number of users in the US in 1876, but these were expensive imported bicycles. High-wheelers were more accessible in the US after Pope started producing Columbias in larger quantities in 1877. Even with Pope improving batch-production techniques, however, Columbia produced about 4,000 ordinaries for adults in 1882 and about 9,000 in 1887.6

The South and Southwest were slow to adopt the ordinary. Texas was no exception; however, there is evidence for some cycling activity there during the high-wheeler era. The earliest documented bicycle club in Texas appeared in a surprising place. San Diego—not the large city in California, but the town west of Corpus Christi, Texas—founded a club on December 17, 1881. The club reported an initial membership of six, including its officers: F. Tiblier, president; F. Gueydan, Jr., vice-president/captain; and George Bodet, secretary. They announced a club uniform composed of a white flannel shirt emblazoned with the club monogram, a matching white helmet, white breeches, and white duck leggings. Meetings were scheduled for the first Saturday of the month at Gueydan’s Hall. Their bicycles were made by Columbia.7

Unlike the boneshaker, New Orleans residents were slow to adopt the high-wheeler. The high-wheeler was mostly ignored in the Crescent City until 1885, but it is also true that some of its residents were cycling in the early 1880s. One cyclist from New Orleans was observed riding the streets of Laredo in 1882. New Orleans resident, Alvan M. Hill (3485) applied for membership with LAW in 1883. The resident of Canal Street in New Orleans was not attached to any local club, though. A cycling group calling itself the New Orleans Bicycle Club was somewhat active during the early 1880s.8

Bicycle Club Membership

The League of American Wheelmen (LAW) issued a brief report of its membership numbers in November 1883. Nationwide, LAW claimed 3,430 members, 654 of whom resided in New York, 556 in Massachusetts, and 473 in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, participation in cycling measured by LAW membership lagged in the South. The two states with the highest memberships were in the Upper South: Kentucky counted 32 members and Tennessee counted 14. Texas reported 5 members and Louisiana reported none. When LAW reported membership in March, national membership increased to 3,598, but none of these new members resided in Texas or Louisiana. Possibly, the New Orleans Bicycle Club was active at the time of these reports, but these club members would only show up as LAW members if they joined the national organization directly.9

Bicycle clubs sometimes constructed identities based on a brand, as with the Victor Bicycle Club which formed in Corpus Christi in 1884. Victor was the bicycle brand of the Overman Wheel Company.10

Roller-skating rinks sometimes doubled as cycling venues in the 1880s. One such example, the Crescent City Roller Skating Rink, occupied an interesting location in New Orleans. The skating rink occupied a lot at the intersection of Washington Avenue and Prytania Street, opposite Lafayette Cemetery, Number One. This venue hosted performances by acrobatic skaters and bicyclists. In addition, the local YMCA opened a new gymnasium early in 1885 with meeting rooms, apartments, and a large second-floor hall suitable for skating and cycling. That year road racing was common in New Orleans, too.11

In a missive published in February 1885, the editor of LAW remarked, “Let me say to those that contemplate visiting New Orleans during the World’s Fair, by no means omit to visit Galveston and its sea bed.” The editor, of course, referred to the World’s Fair in New Orleans of 1884, otherwise known as the Cotton Centennial. The Cotton Centennial opened on December 16, 1884, when President Arthur issued his ceremonial launch of the event. With only two weeks remaining in 1884, the Cotton Centennial was effectively an 1885 event. This raises the question of how the fair might have induced cycling activity, at the very least in New Orleans, but also whether there were spillover effects to Galveston and Houston.12

Although the response to the ordinary was light in New Orleans in the early 1880s, the city witnessed a surge of interest in 1885. The New Orleans Bicycle Club (NOBC) was very active in 1885 sponsoring bicycle races throughout the year. Possibly, the Cotton Centennial contributed to the new interest in cycling as the fairgrounds were frequently a destination of wheelmen, whether as a racing site or as a location for a casual spin. On the evening of February 28, however, NOBC performed an unannounced parade of cyclists with eighteen persons in single file with lanterns suspended from their mounts. After the parade, club members demonstrated some trick riding. Club members trained for races by riding on the fast asphalt surface of St. Charles to the Exposition Grounds. In April, they organized a series of races at the fairgrounds for the Grand Volksfest. A few days later, the club announced its first annual meet, sanctioned by LAW. At the end of 1885, the club organized a New Year’s Eve ride on St. Charles, which already had asphalt paving. There were eighteen cyclists riding, each dressed in a club uniform, some of whom carried fireworks.13

Bicycle racing emerged in Galveston in 1885. At least one bicycle rink was open that year, where cyclists could race. Another event in Galveston combined included both bicycle races and roller-skating races. In addition, a five-mile race in the Island City attracted professional riders from as far away as Massachusetts. Bicycle racing and reporting of the same persisted in Galveston throughout 1885. The Beach Rink was the favorite venue for trick-riding exhibitions. Cycling in Galveston found interesting synergy with other kinds of organizations. The Knights of Labor included a trick bicycle rider as part of the entertainment at its sponsored picnic. When the traveling circus arrived in November, part of the act was the bicycle-riding Melrose family.14

The earliest certain evidence for cycling activity in Houston appeared in 1885, around the same time that Galveston started promoting bicycle races. Gray’s Opera House contained a skating rink, and hosted as a practice venue for a team of cyclists from the Houston Polo Club, including: J. E. St.C. Millard, J. N. Deatheridge, F. T. Shepard, P. H. Thompson, V. W. Anderson, and C. L. Holland. That same group was scheduled on January 25 to participate in a bicycle exhibition in Houston. The opera house rink served as a venue for other cycling exhibitions in 1885. Other cycling events were staged at a second Houston venue that year, the Casino Skating Rink. The combined uses of rinks for skating and cycling were not limited to Galveston and Houston, though.15

The practice of using rinks for skating and cycling events extended to all parts of Texas and even in settlements as small as Luling. San Antonio and El Paso were both home to roller rinks, which also hosted cycling events. Outdoor racing events were somewhat common in San Antonio in 1885. One such event pitted a woman cyclist in a race against a horse. Waco hosted a rink racing event including cyclist, Louise Armaindo.16

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “Bargains—Bargains,” September 5, 1867, newspapers.com [subscription required]; “Grand Bazaar,” December 11, 1867, [subscription required]; [quoted] December 23, 1868, Page 1, Column 3, newspapers.com <https://www.newspapers.com/image/25529637/> [subscription required]; Dale A. Somers, “A City on Wheels: The Bicycle Era in New Orleans,” Louisiana History 8, no. 3 (1967): 222.

Several papers reported on Horace Greeley’s appearance at the Texas State Fair. Greeley’s visit is relevant here because it attracted great interest in the fair among newspaper editors; therefore, the general coverage of the event was sufficient enough that the velocipede race should have been reported if it had occurred. Here are a few examples: Tri-Weekly State Gazette (Austin), “State Fair,” May 26, 1871, Portal to Texas History; Dallas Herald, “Something about Texas—Its Political Condition,” June 17, 1871, Texas Portal to Texas History; The Morning Star and Catholic Messenger (New Orleans), “Miscellaneous,” May 28, 1871, newspapers.com [subscription required]. For more on Greeley's visit to Houston, see C. Richard King, "Horace Greeley in Texas," The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 64, no. 3 (1961): 333–41. None of these included any results of the velocipede race, nor confirmation that one had taken place. It seems implausible that the velocipede race occurred and there are no surviving reports of it. The event was most likely cancelled due to the condition of the race course.

Flake’s Daily Bulletin, (Galveston, TX), “Houston Local News,” May 25, 1871, NewspaperArchive <Stable URL> [Accessed December 1, 2024]. There are no surviving records for the Houston Telegraph and Register for May 25 – June 5, 1871 at Houston History Research Center.

Galveston Daily News, “Houston Local Items,” June 29, 1875, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth461391/m1/4/> [Accessed December 1, 2024].

Epperson, Peddling Bicycles to America, 7, 23‒4. Herlihy, Bicycle: The History, 178 notes that ordinaries were imported to the US as early as 1873. There is no evidence that these were imported in significant numbers until 1876.

Somers, “A City on Wheels,” 222; Epperson, Peddling Bicycles, 55‒7; Herlihy, Bicycle: The History, 182‒99.

Bicycle World and the LAW Bulletin, “San Diego,” 4 (April 7, 1882), 256‒7, Smithsonian Libraries Online.

Somers on the highwheeler: Bicycle World and the LAW Bulletin, 5 (June 23, 1882), 405, Smithsonian Libraries Online <https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/bicyclingworld51882bost>; Bicycle World and the LAW Bulletin, “Applications,” 6 (March 23, 1883), 242, Smithsonian Libraries Online; Bicycle World and the LAW Bulletin, 7 (August 3, 1883), 157, Smithsonian Libraries Online < https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/bicyclin1018841885bost>.

Bicycling World and the LAW Bulletin, 8 (November 30, 1883), 45, Smithsonian Libraries Online <https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/bicy111885bost>.

Bicycling World and the LAW Bulletin, “Wheel Club Doings,” 9 (June 27, 1884), 136, Smithsonian Libraries Online; Herlihy, Bicycle: The History, 229.

Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “Opening of the Skating Rink,” January 11, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Democrat (New Orleans), “The Crescent City Roller Skating Rink,” January 5, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “A Model Gymnasium,” January 11, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Bicycle. Coming Wheel Races,” January 25, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times Picayune (New Orleans), “The Bicycle: A Letter from Champion Prince,” January 31, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “Bicycle: Coming Wheel Race,” February 12, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription].

Quoted Bicycling World and the LAW Bulletin “The Professionals at Galveston,” 10 (February 13, 1885), 249, Smithsonian Libraries Online; Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), 382.

Somers, “A City on Wheels,” 222‒3; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Wheel. A Meet of the New Orleans Bicycle Club,” March 2, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Bicycle: Morgan and Prince Matched,” March 6, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Bicycle. Fast Time by Prince at West End,” March 9, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Wheel. Activity Among the Local Bicyclists,” April 18, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Wheel. Coming Bicycle Events,” April 25, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “Grand Volksfest,” April 26, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Wheel. The First Annual Races of the Bicycle Club,” April 30, 1885, newspapers.com [subscription required]; Times-Picayune (New Orleans), “The Wheel. A Celebration on Bicycles,” January 5, 1886, newspapers.com [subscription required]. The club headquarters were located at 180 St. Charles Avenue.

Galveston Daily News, “Stray Notes,” “The Rink,” “Rink Races To-night,” January 10, 1885, Portal to Texas History; Galveston Daily News, “The City,” January 12, 1885, Portal to Texas History; Bicycling World and the L.A.W. Bulletin, 10 (February 6, 1885), 232, Smithsonian Libraries <https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/bicyclingw1018841885bost>; Galveston Daily News, “The Great American Bicycle Combination,” February 2, 1885, Portal to Texas History; Galveston Daily News, “Stray Notes,” March 26, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth464476/m1/8/> [Accessed December 1, 2024]; Galveston Daily News, “The Trinity Church Guild,” May 1, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth462416/m1/10/> [Accessed December 1, 2024]; Galveston Daily News, “List of Prizes,” July 7, 1885, Portal to Texas History) <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth462661/m1/8/> [Accessed December 3, 2024]; Galveston Daily News, “The Circus,” November 7, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth464739/m1/8/> [Accessed December 1, 2024]; Evening Tribune (Galveston), “Beach Roller Skating Rink,” November 27, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1132371/m1/4/> [Accessed December 1, 2024].

Galveston Daily News, “The Houston Polo Club,” January 24, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth464495/m1/3/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; Galveston Daily News, “Bayou City Locals,” February 1, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth464188/m1/3/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; Galveston Daily News, “State Press,” March 28, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth463332/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]. Gray’s Opera House was located on the west side of Fannin Street between Congress and Preston avenues, facing the Harris County Courthouse. “Block 32,” 1885 Houston Sanborn Map, Facet 9 (Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Digital Archives <https://maps.lib.utexas.edu/maps/sanborn/g-i/txu-sanborn-houston-1885-09.jpg> [Accessed December 2, 2024].

Galveston Daily News, “State Press,” March 28, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth463332/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; San Antonio Light, “Rays of Light,” February 3, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth163082/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; El Paso Daily Times, “Local Gatherings,” March 12, 1885, newspapers.com <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth501740/m1/4/> [Accessed December 3, 2024]; San Antonio Light, “Fun at the Driving Park,” February 14, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth163092/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; San Antonio Light, “The Races,” February 16, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth163093/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; San Antonio Light, “Rays of Light,” February 24, 1885, Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth163101/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; San Antonio Light, “Rays of Light,” February 19, 1885, Page 4, Column 3 Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth163096/m1/4/> [Accessed December 2, 2024]; Waco Daily Examiner, February 28, 1885, “At the Rink Last Night,” Portal to Texas History <https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth114137/m1/3/> [Accessed December 2, 2024].