Image 1. Henry B. Winbush, “Le Botteghe di Gioielleria sul Ponte Vecchio,” post card, The Newberry Library, via Internet Archive.

On Tuesday, I considered pre-industrial streets as they were used in ancient Rome. Pre-industrial is an old term and its meaning in history is uncertain, but I am using it away. Anyone who has suggestions for improving the language here is welcome to leave a comment. I claimed that pre-industrial streets support a “greater range of public uses, implying that people used them in many ways in which people now use modern parks.” I distinguished them from modern streets, which like the utility conduits that operate below them, are optimized for movement.

In ancient Pompeii, planners sometimes plopped a water fountain or a religious shrine in the middle of an intersection. Not only were these fixed objects hindrances to movement, they induced crowds, who often lingered in the streets near these amenities. Throngs of lingering people created an even more severe hindrance to movement adjacent to these amenities. Examination of ancient Pompeii, however, is like the drunk looking for his lost keys underneath the street lamp: it is looking where the information is already most abundant. We should look at other urban sites of Europe from different eras and look to urban sites in other parts of the world. If anyone has any examples of pre-industrial streets from archaeological or historical studies, please leave a comment.

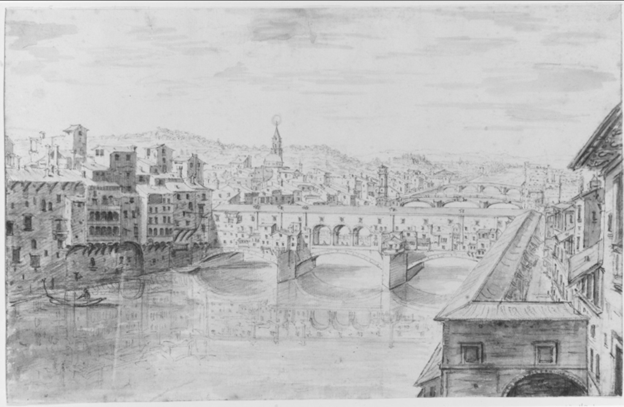

Image 2. Jacques Callot, “The Ponte Vecchio, Florence,” Print, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Leonard F. Fuller, Jr., in memory of Mila Bomgardner Leuthold.

One set of possibilities for study of pre-industrial streets in medieval and early modern Europe are urban bridges. Ponte Vecchio in Florence is an example of such as bridge from the late-medieval period. By contrast, Pont Neuf is an example of a modern bridge from the early modern period, though I exaggerated the historical significance of its design. Real estate development was a common strategy for financing urban bridges. Examples of developed bridges are London Bridge, Ashun Bridge in China, Ponts des Marchands in France, and Krämerbrücke in Germany.

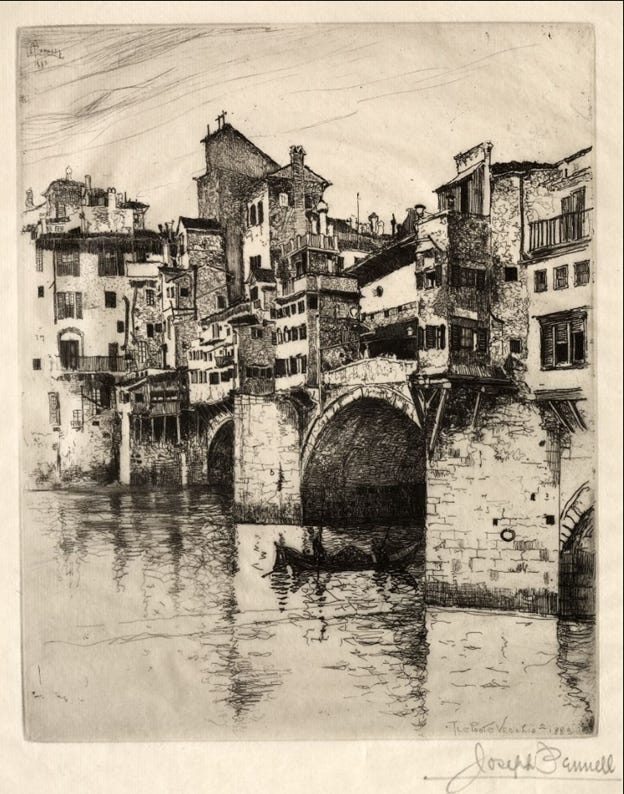

Image 3. Joseph Pennell, “The Ponte Vecchio,” Engraving, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH, Gift of George A. Goddard.

Ponte Vecchio was first constructed as early as 1345. With an unknown completion date, it is not clear that the original design included buildings along its flanks. Giovanni Villani (d 1348) wrote that the 43 shops on Ponte Vecchio contributed no less than 80 gold florins to the city’s treasury annually, while Marchione di Cappo Stefani claimed that bridge revenue was sufficient to pay for construction costs within twenty years.1

Including buildings on a bridge is a pre-industrial notion. It effectively re-imagines a bridge as any other pre-industrial, multi-functional street. It makes a bridge into a place. As with David J. Newsome’s interpretation of Varro, it makes a bridge into a location that facilitates movement and lingering. The buildings are reasons for stopping and lingering. As more people stop and linger on the bridge, however, it becomes more crowded, impeding movement across the bridge. Thus lingering and moving are always in conflict, forcing a compromise wherever lingering is permitted. Urbanism implies accepting these compromises.

Image 4. Israel Silvestre, “View of the Ponte Vecchio, Florence,” Drawing, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Charles S. Whitney, Bridges: Their Science and Evolution (New York: Greenwich House, 1983), 107; Theresa Flanigan, “The Ponte Vecchio and the Art of Urban Planning in Late Medieval Florence,” Gesta 47, no. 1 (2008): 4, 14 n9, n10.