Other essays in the series:

Streets of Deadwood: The Throughfare

Streets of Deadwood: “The City Is as it Walks”

Streets of Deadwood: A City Not Yet Civilized

Waking and Sleeping in the Streets of Deadwood

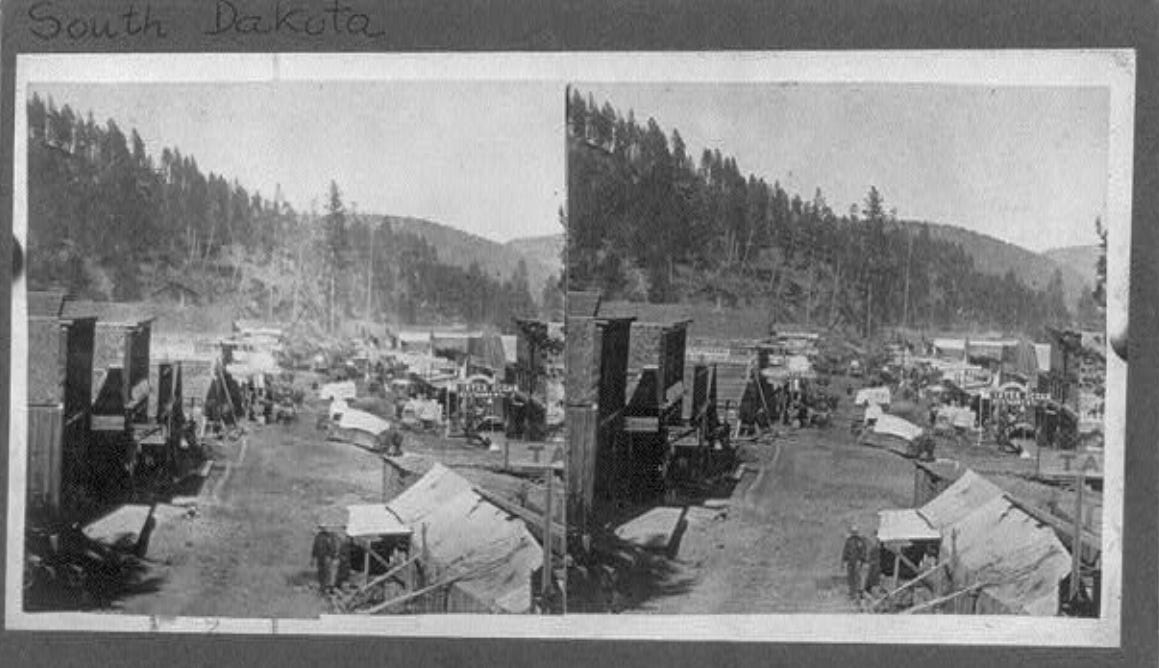

Image Source: “Deadwood, South Dakota, 1876,” Library of Congress, originally published c. 1908.

Introduction

The HBO series Deadwood could be the best scripted American television series of all time. Film and television critics Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz rated Deadwood as the tenth best production of this type.1 My interest in Deadwood for present purposes is the presentation of the town and its nameless main street. Milch makes not Wild Bill, Calamity Jane, or Seth Bullock the main character of the show. Deadwood is the star of Deadwood.2 Rather, Main Street is the star of Deadwood. Yet Milch does not endeavor to portray a historicism of “the camp,” as it is most often referenced within the show’s dialogue. Instead, he builds a Deadwood based partly on history and partly on fictions which create “historical distance.” Milch’s main interest is the exploration of a society constructed in the absence of law and political structure, which is populated by a cast of characters with dark pasts.3

I expect that some aspects of the show’s depiction of the streets are historically accurate and others are not. The fourth episode of the series, “Here was a Man,” includes the murder of Wild Bill Hickok, which occurred in the historical Deadwood of 2 August 1876, the same year that Alexander Graham Bell built his first working telephone. The same year, Frederick Law Olmsted pitched his concept for the “Emerald Necklace” park system to the city of Boston. Albert Pope, the founder of Columbia Bicycles, attended the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, where he perused the collection of English mounts. Prior to 1876, Bostonians already had the options of traveling within the city by omnibus and horse railway, and to the suburbs by steam locomotive. New York and Boston each had its own robust network of horse railways. Yet these people in these technologically advanced cities still valued and used streets in similar ways as streets of pre-industrial cities were used. The historical Deadwood, with its small urban footprint, did not require rapid mobility for transport, thus it would have been easier to preserve characteristics of pre-industrial streets.4

I am concerning myself less with sifting out the anachronisms than with examining Milch’s Deadwood on its own terms.[5]5 What is its street life? How are characters defined in terms of their behavior in the public way? How do characters react to being under observation and scrutiny while using public space? What are the physical characteristics of the street? How do people use the street? In what ways do people attempt to control public space? In many respects, the streets of Deadwood have the characteristics of those from pre-industrial cities. Such similarities owe less to design and construction; instead, they are related to pre-industrial ideas regarding the purposes of streets.6 In some cases, I compare and contrast the streets of Deadwood with the social history of Rome.

Two Streets in the Pilot

There are two representations of streets in the series pilot. The first is a portrayal of an unnamed town in Montana. There is a single torch light outside. There is a Feed and Grain store. To the left is a partial view of a covered boardwalk. The dirt street surface is dry, smooth, and flat. The saloon to the right is neatly faced in brick. It is not aligned with the other buildings and is not perpendicular, either. Its windows are illuminated with large candles. There is a wagon parked in front. There is a pole in the street, representing the only encroachment to the thoroughfares. Only one person is visible outside. He is keeping his mount to a walking pace.

About a dozen men armed with rifles assemble outside the jail. Half of them bear torches. One calls out to Sheriff Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant). This is a lynching party. Its leader is insulting and threatening the sheriff, and demanding that Bullock hand over the prisoner at pain of death. Sol Star (John Hawkes) emerges from the alley in a heavily-laden wagon, training his own rifle at the lynching party.

Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz, TV: (The Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2016), 69.

Mark Singer, “The Misfit.” The New Yorker. 6 February 2005; Sepinwall and Zoller Seitz, TV: The Book, 70.

Matt Zoller Seitz, The Deadwood Bible: A Lie Agree Upon (New York: MZSPress, 2022), 72.

Library of Congress, “Landscape Architect for the Nation, 1865-1903.” Retrieved 20 May 2019; Bruce D. Epperson, Peddling Bicycles to America: The Rise of An Industry (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2011), 23; Sam Bass Warner, Jr. Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870–1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978, second edition), 15–7; Clay McShane, Down the Asphalt Path: The Automobile and the American City (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), on characteristics of preindustrial cities, 1–2, on transportation development in New York and horse railway in general, 12–5; Gideon Sjoberg, The Preindustrial City: Past and Present (New York: The Free Press, 1960).

Though not relevant to the topic at hand, Milch’s introduction of the bicycle in season two is more color than history. Tom Nuttall (Leon Rippy) receives delivery of a high-wheel bicycle. During the period represented in the show (1876–1878), virtually all bicycles were imported from England. Even Albert A. Pope of Columbia Bicycle fame began as an importer of British-made bicycles. Nuttall referred to his new contraption as a “boneshaker.” The boneshaker refers to machines based on the Lallemont design. His machine would have been known as a “wheel,” “high-wheeler,” or “penny farthing.”

For the purposes of streets, see McShane, Down the Asphalt Path, 57-80; Peter D. Norton, Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 2-7.