What Is a "House"? Provisioning Food

Small home-based businesses supplemented the large public market

Other Posts in the Series

What Is a “House”? Definitions

What Is a “House”? Hotels and Boardinghouses

What Is a “House”? Provisioning Food

What Is a “House”? Domestic Architecture

The Social Inversion of “Dining Out” and “Eating at Home”

At the heart of the present-day meaning of the home is home-cooking: the idea that we eat where we reside. Historically, it was less common to eat in one’s dwelling, and cooking was a specialized skill, so cooking for oneself was even less common. In ancient Roman Italy, for example, eating at home was socially inverted: people residing in elite households dined in their domus; the masses who resided in apartments provisioned water and food in the streets or in taverns. Literary evidence for street life in Rome is complemented by archaeological evidence in Pompeii. Katie Rawson and Elliot Shore claim that private kitchens were still uncommon in the nineteenth century. It would be interesting to study the prevalence of cooking and kitchens through proxies such as household size and boarding, and to the study the social inversion of eating at home in the nineteenth century.1

Markets and Grocers

Grocers are commercial establishments. When grocers operated their business on their homesteads, they combined the functions of residence and business, consumption and production, and domestic and commercial. House in present-terms is a synonym for home, with both words implying the polarity of residence, consumption, and domestic versus business, production, and commercial.

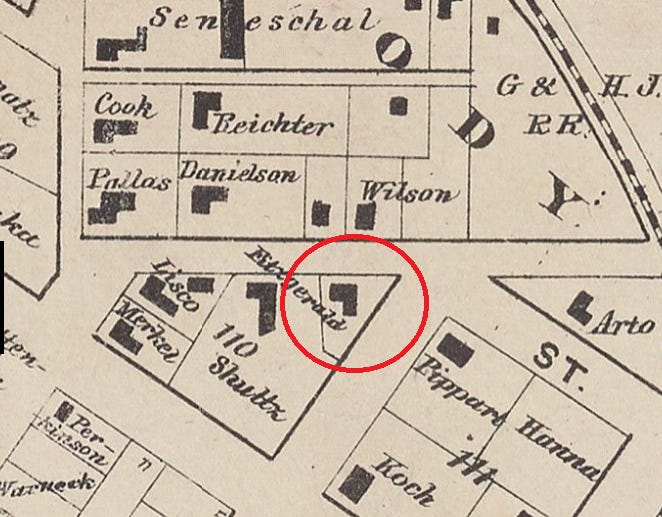

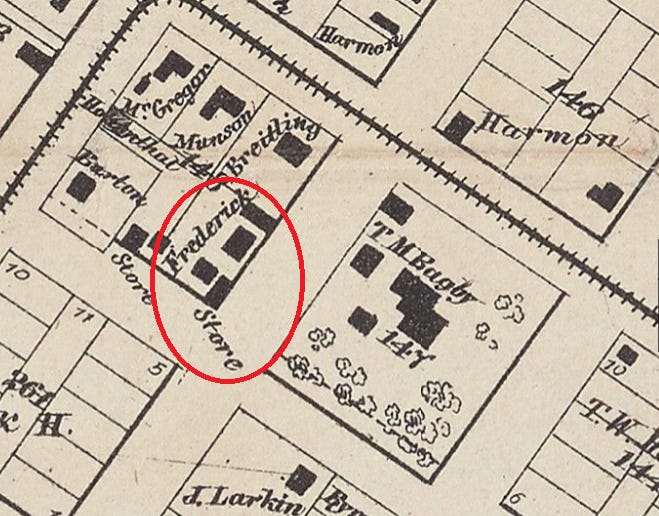

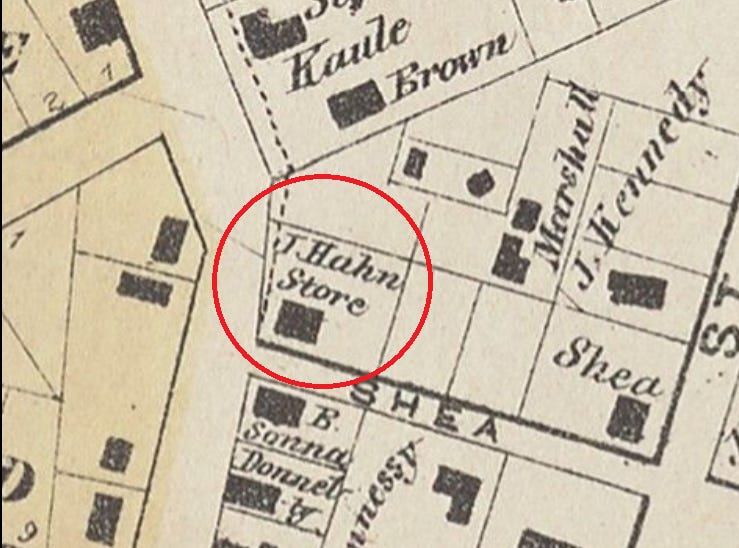

For those who did provision food for their houses—whether private or public—the central market served as a hub for food distribution in many settlements. Gergeley Baics studied the public markets of New York City. The city added public markets as the city expanded geographically, and gradually the public market system was replaced by small private grocers. The large public markets made sense as a logistical node: instead of out-of-town carriers making bulk deliveries throughout the city, each could deliver to a single well-known location. In ancient Rome, this was the Forum Boarium, a warehouse complex in the southwest of the city, directly accessible from the Tiber River and the Pons Aemilius, and indirectly accessible from Porta Capena and Porta Lavernius. Yet the Forum Boarium not located centrally within the city. What was accessible for freight carriers was not so accessible to the most populous districts in Rome, thus its advantage on location to shippers proved to be a liability to Roman consumers. This dilemma was resolved through an informal secondary food marketing system of taverns, peddlers, and hawkers, who all expected to sell food at a profit, but added value by distributing the food to where it was needed. Secondary sellers were distribution conduits for bulk and unprepared food in nineteenth-century American cities as well, though by the late 1800s, these were almost exclusively neighborhood grocers. At the same time, many of these owners operated their groceries at their homestead, even combining residence and business in the same house. Many Houston grocers were still residing on the business premises, even as late as 1870. The 1869 Wood Map depicts the footprints of many buildings in Houston, including these grocers, which can be identified through the 1870 city directory. Not only do the two-dimensional forms on the map fail to conform to present-day expectations of commercial buildings, in four of the five examples, these properties are labeled as “stores” (Image 1–4). Yet these “stores” are not purely commercial in function.2

Image 1. W. E. Wood, “Map of the City of Houston, Sheet 3,” 1 January 1869. The grocery and homestead of MC Fitzgerald in the Second Ward, at the edge of the Frosttown subdivision. Image source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, Digital Archives. Annotated by author.

Image 2. W. E. Wood, “Map of the City of Houston, Sheet 4,” 1 January 1869. The grocery and homestead of William J Frederick in the Fourth Ward. Image source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, Digital Archives. Annotated by author.

Image 3. W. E. Wood, “Map of the City of Houston, Sheet 2,” 1 January 1869. The grocery and homestead of A Schilling on Montgomery Road in the Fifth Ward. J Kaule also operated as a grocer in this neighborhood, but there is no confirmation that he resided there as well. Image source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, Digital Archives. Annotated by author.

Image 4. W. E. Wood, “Map of the City of Houston, Sheet 2,” 1 January 1869. The grocery and homestead of J Hahn in the Fifth Ward. Image source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, Digital Archives. Annotated by author.

Mary Beard, The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found (Cambridge, Belknap Press, 2008), 57–8; Jeremy Hartnett, The Roman Street: Urban Life and Society in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 60–4, 67; Claire Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Katie Rawson and Elliot Shore, Dining Out: A Global History of Restaurants (London: Reaktion Books, 2019), 14, 16; bnjd, “Residential Hotels and Boarding Houses,” 2 February 2021, What Are Streets For.

Gergeley Baics, Feeding Gotham: The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York, 1790–1860 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); Cindy R. Lobel, Urban Appetites: Food and Culture in Nineteenth-Century New York (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014); Gloria L. Main, “Women on the Edge: Life at Street Level in the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 32, no. 3 (2012): 332. Ancient Rome: Claire Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 56–7, 93, 159–60. Houston grocers: William Murray, compiler, General Directory for the City of Houston, 1870–1 (Houston: William Murray, 1870), 35, 53, 81.